Since March/April, I have been sitting on my hands not quite ready to hit the “Publish” button to push my words off onto the instantaneous online press. But as time passes by, I am losing the details of the what, why, how of my GitHub data explorations and going back through my GitHub history to identify my work processes requires more and more mental aerobics. Hence, while I am still in a state of partial clarity, I will do my best to squeeze out my months-past thoughts during an afternoon writing spurt.

* * * Here I go! * * *

Wanting to have fun exploring GitHub data, I headed first to the playground: GitHub’s API. It had all that I could want for my preliminary explorations. I could grab data on repository languages, pushes, forks, stars, etc. You name it. Problem was it was like standing at the base of a bouldering wall, positioning yourself in your first hanging form, and then not knowing how to reach the next boulder on the colored route. My technique was not quite even a V0 and my arms were too weak to compensate by just pulling myself up through sheer muscle.

That’s when I found GitHub Archive. GitHub Archive is a “project to record the public GitHub timeline, archive it, and make it easily accessible for further analysis.” With the data hosted on Google BigQuery, the GitHub event data was readily available to be queried using SQL.

SQL! SELECT statements! I can do that!

I decided to go ahead and first explore GitHub’s data via GitHub Archive. The API would have to wait.

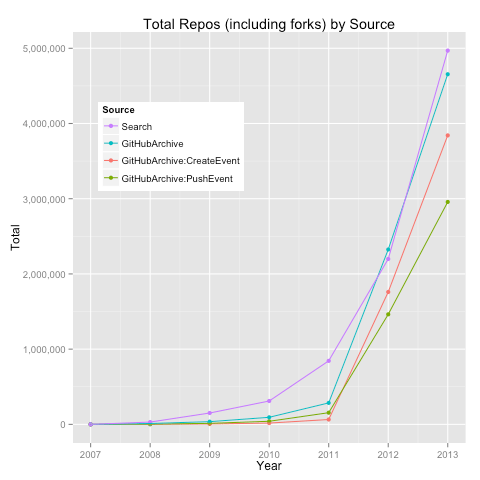

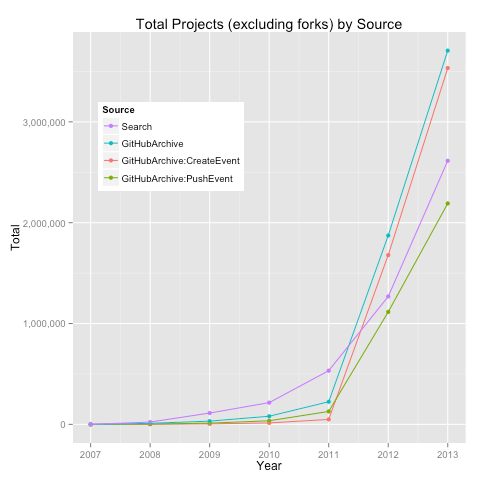

I started out with a basic question: What is the growth trend of total GitHub repositories? What is the growth trend of total GitHub projects i.e., repositories excluding forks?

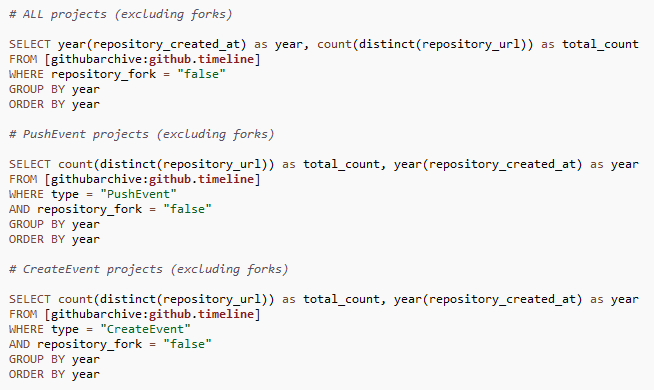

To answer these questions, I parsed the GitHub Archive data in three ways:

- GitHub Archive

- GitHub Archive: CreateEvent

- GitHub Archive: PushEvent

Side Track: CreateEvent vs. PushEvent

The reason why I looked at both CreateEvent and PushEvent was to investigate the peculiarities that emerged when running my initial query for the number of repositories by programming language and creation date, restricted only to CreateEvent. Looking for whether anyone else had run a similar analysis on which I could compare my results, I stumbled upon Adam Bard’s blog post “Top GitHub Languages for 2013 (so far)”.

Here was his query.

This query was similar to mine but after exploring the data more closely, I had a couple issues with this approach. Although it may be difficult to see without looking at the raw data structure, the questions that popped up were:

- Wouldn’t counting non-distinct languages i.e., count(repository_language) result in duplicate counts of unique repositories?

- Shouldn’t we be looking at only CreateEvent’s payload_ref_type == “repository” rather than also including branches and tags?

- Don’t we have a “null” issue for repository language identifications of CreateEvents?

- over 99% of CreateEvents with payload_ref_type == “repository” have “null” repository language

- over 60% of CreateEvents for all payload_ref_type {repository (>99%), branch (~28%), tag (~57%)} have “null” repository language

Example

Let’s look at the Ceasar’s repository “twosheds”.

If we count using count(repository_language), we would have the following total counts by language:

- Python: 14

- null: 1

Now this seems wrong. Why would we count these records multiple times as unique repositories? Instead, these should fall under one repository count for “twosheds” and be categorized as written in Python. What if we restrict the query to only CreateEvent’s payload_ref_type == “repository” and count as count(distinct(repository_url))? The issue here is that the assigned language is now “null”.

Sure, we could think of ways around this — for example, take the maximum non-missing language identification for each unique CreateEvent’s repository URL, regardless of the payload reference type. However, given the prevalence of “null” language identifications for CreateEvent, why not try PushEvent instead? We can check if PushEvent has similar missingness with its repository language identifications. If not, under the assumption that active repositories are pushed to, we can count the distinct repository URLs of PushEvents to identify unique repositories by creation date and programming language.

Indeed, only ~12% of PushEvents have “null” repository language identifications. PushEvent seems to be good alternative!

Back on Track & Back to Basics

Let’s go back to our initial question: What is the growth trend of total GitHub repositories? What is the growth trend of total GitHub projects i.e., repositories excluding forks? I computed the yearly totals using count(distinct(repository_url)) to count the total number of unique repositories by creation date (year).

As a litmus of sorts, I compared these yearly counts to those from GitHub Search.

What do we notice here?

Assuming GitHub Search as the barometer of expectation:

- prior to 2012, GitHub Archive (all, CreateEvent, PushEvent) seems to produce underestimates of total repositories and projects

- repositories: Search ~ GitHub Archive (all)

- projects: Search ~ PushEvent

Now, why do we observe these differences?

I mulled over the observed differences, raising my stack of questions higher. What is going on here? How will it affect my analyses?

For now, I will leave it here and continue next time with more on the GitHub analysis I ended up pursuing.

As I say adieu, I ask: What interesting or curious things do you notice here so far?